Inspired by recent Coventry Society visits and his own reseach, historian and Coventry Society Committee member, David Porter, tells us about the history of sewage disposal in Coventry. David writes…..

“Sewage Disposal is a Subject of Very Great Interest”

While writing a paper in 1946, C R Deeley – Chief Assistant to Coventry’s Sewers and Sewage Disposal Department – advanced this admittedly rather unlikely statement. For its part, this short historical overview will attempt to persuade the sceptic that there might indeed be some basis to his claim, particularly in light of the difficulties posed in this regard by the five-fold increase in Coventry’s population from approximately 70,000 in 1901 to nearly 350,000 by 2021.

To put into context the city’s earliest attempts at dealing with the waste it produced, the new Coventry Board of Health set up in 1849 established that of the city’s 98 streets only 15 were sewered at that time, while the district of Hillfields for example was reported to have no sewers or even cesspits at all with waste simply dumped in the streets. What sewers were in existence then emptied via 21 outlets directly into the River Sherbourne, and so it is perhaps little wonder therefore that Coventry was subject to repeated outbreaks of cholera at this time.

In response, by 1852 the Corporation had laid out a city sewer system which resolved these issues by the simple expedient of carrying the waste a mile south of the city’s boundary and discharging it further downstream into the River Sherbourne. According to one commentator in 1870, this method “soon converted the river into a large, open and extremely offensive sewer, which finally entered the River Avon and contributed towards the supply of drinking water to the town of Warwick.”

In response to such understandable objections, in 1874 a Court of Chancery injunction ordered that this practice cease, prompting a private company to set up a treatment plant at Whitley with a plan to sell treated sewage sludge for use as fertiliser. Just two years later, however, this scheme collapsed and the Corporation assumed responsibility for the site instead, treating the sewage from the city – amounting to 2 million gallons per day — with a mix of chemicals and employing a technique called broad irrigation, whereby the sewage was spread across eight acres of land in adjoining fields.

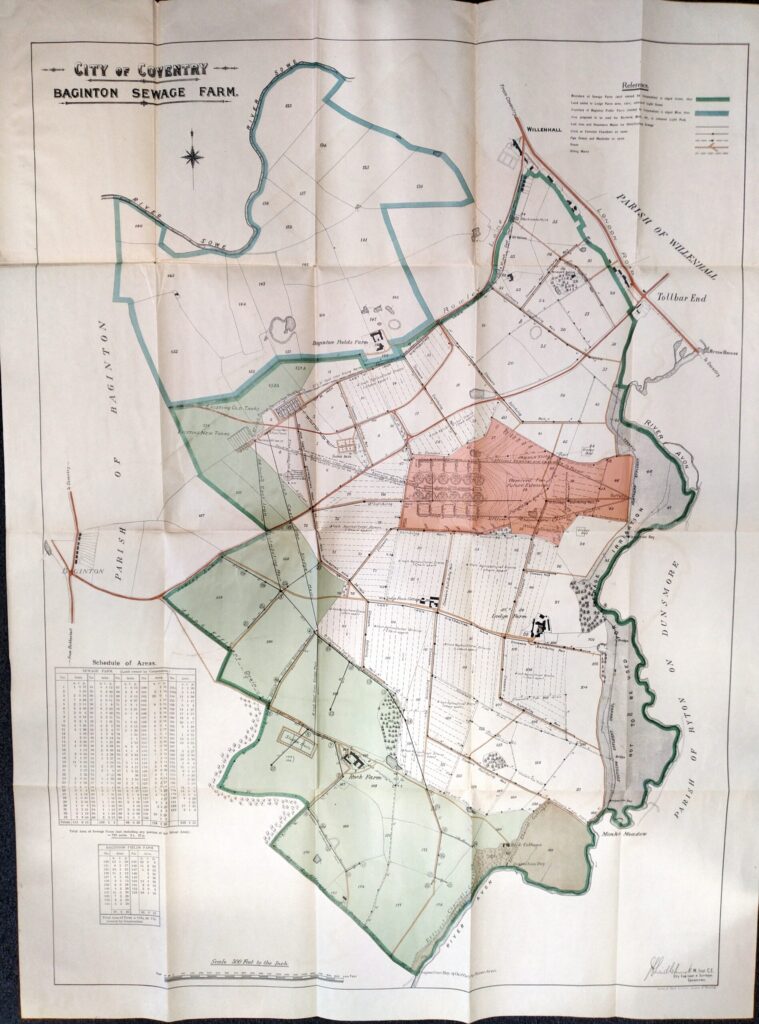

Unfortunately, this system was soon overwhelmed by the expansion of the city’s population, which grew from approximately 42,000 in 1881 to nearly 70,000 in 1901. In consequence, after much debate the Council arranged for the purchase of 500 acres of agricultural land at Baginton in 1896, the great majority of which was to allow for more broad irrigation processing. Clearly, this was a huge increase on the land available at Whitley, although one major issue with this new scheme was the fact that the sewage now needed to be pumped uphill from Whitley to Baginton by a steam-powered pumping station, which started operation on 3rd February 1901.

With this momentous decision taken, a reporter with the Coventry Herald – clearly not of the same persuasion as C R Deeley above – was moved to opine that “an end of a weary business is thus in sight” and yet nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, as early as 1908, with the population estimated to have grown again to 91,000, the Corporation decided it would need to purchase an additional 250 acres in order to extend this new facility. In spite of this, when he reported back on progress with this extension in 1912, City Engineer J E Swindlehurst estimated that the population was already in excess of 111,000 and further concluded on this basis that by 1914 the city would find itself “back to the position of 1908, when the conditions were considered to be such as to justify extensions being carried out.”

Indeed, even these projections fell short of the actual population total of about 120,000 at the beginning of the Great War, during which time the huge numbers of munition and other workers pushed this number at one stage to a peak figure in excess of 142,000, resulting in a sewage volume of 5 million gallons per day.

Perhaps all too predictably, this incessant growth started to outstrip the capacity of the broad irrigation scheme at Baginton, and so new techniques were adopted such as the use of large bacteria beds stored within large cylindrical tanks, twelve of which were finally installed by the year 1919 to be used in conjunction with the existing irrigation fields.

(While it should be emphasised that this paper – like its author – is not technical in nature, it is worth pointing out that calculations at this time showed that the amount of sewage which could be treated over an area of 450 acres by means of broad irrigation would require only 10 acres if bacteria beds were employed instead, an effective demonstration of the benefits of technological development and a significant consideration for a city whose population had grown so strikingly in such a short time.)

Notwithstanding the further benefits to be gained by the introduction in 1925 of another technological advance involving an activated sludge process at Baginton, the city underwent another period of expansion largely owing to boundary extensions in 1928 and again in 1932. These changes raised the city’s population to 182,000, which boosted the daily sewage flow to 6 million gallons per day. To compound the difficulty this presented, many of these new areas of the city were not connected to the pumping station at Whitley, which it will be remembered pumped the city’s sewage up to Baginton. To add a political dimension here, the agreement of Warwickshire County Council to the transfer of these districts was in fact to a large extent contingent upon Coventry Council agreeing to connect the new areas in question to the city’s sewage system.

In response to these issues, in 1928 the City Council accepted advice from its new City Engineer – namely E H Ford — that a new disposal facility with 18 bacteria beds should be built near Finham Bridge, which could receive half of the city’s sewage via two new gravity-fed sewers laid out along the River Sowe and the Canley Brook valleys, with the remainder of the sewage continuing to be pumped from Whitley to Baginton where the old irrigation fields would be abandoned but the bacteria beds and the activated sludge plant would be retained.

This new facility at Finham – on the site still used today – was officially opened on 29th September 1932, and yet – as the reader will have already predicted – the growth of the city’s population continued unabated to such an extent that within three years Finham was receiving an additional flow of 2 million gallons per day. As so many times before, the city authorities were required to increase the capacity of the new facility, and by the time the extended site was officially opened on 10th June 1936 Finham had been equipped with a further 17 bacteria beds, bringing the total number to 35.

Plans for further change were drawn up at this time to close the Baginton facility but these were cancelled owing to the Second World War, by the end of which the population had risen yet again to around 230,000 with the total sewage flow amounting to 10 million gallons per day, both figures double those recorded during the First World War. This situation was exacerbated by the fact that the composition of the sewage itself was affected by the considerable growth in the number of factories at this time, which gave rise to more chemical waste entering the system.

Already it was clear that neither Baginton nor Finham could be enlarged again and so new strategies were adopted to increase the efficiency of the existing plants. The first of these involved a new method called partial purification allowing the activated sludge and bacteria bed facilities to be used in tandem, resulting in a 50% increase in capacity. Secondly, in order to stagger the flow of sewage – unsurprisingly, the rate of flow varies considerably at different hours of the day – a so-called recirculation technique was introduced at Finham in 1945 which allowed the flow through the facility to be varied so as to accommodate these fluctuations and thereby in effect boost the plant’s capacity further.

Another technological change adopted in the 1950s at Finham which had also been the subject of wartime experimentation involved the practice of heating the sludge in the bacteria beds, which revealed that the capacity of the plant could in theory be doubled. To help mitigate the cost of this, the methane gas given off during the process was used to operate the heaters and even to generate electricity for use on the site – interestingly, in 1943 an attempt had even been made to use the gas as an alternative fuel for use in cars but despite the project displaying early promise the newly-formed Ministry of Wartime Transport would not support further development.

Moving forward to 1960, with the city’s population already exceeding 300,000, the Coventry Evening Telegraph reported that the city’s sewage flow had increased from 14 to nearly 20 million gallons per day, in part the result of the decision to include much of Bedworth as well as rural areas near Meriden, Warwick and Rugby within the Finham drainage area. This latest expansion resulted in a plan to double the capacity at the Finham site by 1965 and to allow for the long-anticipated closure of the Baginton sewage treatment facility.*

In parallel with this development, to help avoid issues with flooding caused by heavy rain the Corporation also undertook the huge task of duplicating the sewer system feeding into Finham which involved the construction of almost 50 miles of additional sewer pipes between 1960 and 1983, necessitating an expenditure of £65 million.

After responsibility for sewage treatment in Coventry returned to the private sector in the guise of Severn Trent plc in 1989, the now redundant bacteria beds at Finham were replaced over the following ten years with a new activated sewage plant to help the company meet enhanced treatment standards.

Thanks primarily to the introduction of such new technology and treatments, it can be argued that the start of the new millennium marked a real turning point by bringing to an end the constant cycle outlined above, whereby the capacity of the city’s sewage disposal facilities was increased only for this to be outstripped in just a few years or even months by continued population growth.

In fact, with the plant now serving a regional population of 500,000 and dealing with some 22 million gallons (or about 115 megalitres) of sewage per day, the process of heating the sewage has been further developed with the construction in 2023 of a new thermal hydrolysis plant at Finham allowing for significantly greater production of biogas, which in addition to helping to meet energy needs onsite can now also be exported to the grid to be used elsewhere. To add to this, in spite of this further increase in scale, because of the greater efficiency of these processes significant areas of the site are now no longer needed and so are undergoing a process of rewilding.

In closing, the intention in this article has been to show how Coventry has attempted repeatedly to develop one aspect of its essential infrastructure to cope with the seemingly inexorable growth of its population during much of the last century and a half. On the basis of this overview, the reader will no doubt have already formed their own judgement as to whether sewage disposal is to be viewed as “a weary business” or “a subject of very great interest” but hopefully this article has gone some way at least to help promote the latter view.

*In the interest of full disclosure, one part of the Baginton site at Rock Farm was responsible for dealing with sludge from both sewage works, allowing this to be used as agricultural fertiliser. Today this is all processed exclusively on the Finham site to produce what is euphemistically termed ‘cake’ for use on farmland as before but Rock Farm did not finally close until 2013, a full century after it first came into operation.

Some notes

The photographs and the plan of the Baginton sewage facility are used with the permission of the Coventry Archives while the Ordnance Survey map extracts are reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) licence.

The choice of subject matter for the article was inspired by my involvement with cataloguing City Engineer photographs from the Finham sewage works as part of my volunteer duties at the Coventry Archives as well as a neat coincidence concerning a number of Coventry Society visits over the course of the past year as follows:

Segro Park, 12 June 2023 – near the former Baginton sewage works

Sherbourne Recycling, 13th February 2024 – near the former Whitley sewage works

Finham Wastewater Treatment Works, 2nd August 2024 – on the same site since 1932

David Porter

September 2024