Historian and CovSoc Committee member, David Fry, has been studying past editions of the Alfred Herbert Newsletter. These newsletters are much more than just a works newsletter and reveal a lot about the thinking in the city in the post-war years as the city was rebuilt. The article below is extracted from 1956 editions of the newsletter, in the words of the author.

At least it began pleasantly for in the New Year’s Honours List there appeared the names of William Lyons, Founder, Chairman and Managing Director of Jaguar Cars Ltd., who received a knighthood, and Dr A. H. Marshall, the City Treasurer, who was made a C.B.E.

For the more romantically minded there was also a pleasing piece of news for on 6 January came the announcement of the engagement of Miss Grace Kelly to Prince Rainier of Monaco.

Perhaps the only disappointment was that occasioned to the younger generation by the new Astronomer Royal who said in no uncertain terms “talk of interplanetary travel is utter bilge and all rather rot”. Not that he was believed, of course. . . .

Later in the month it was officially announced that Her Majesty the Queen would lay the foundation stone for the new Cathedral on 23 March. At the same time the Corporation made known its plans for the building of a new one exchange in Little Park Street at a cost of £1,000,000.

The fact that a rise in the rates was also announced occasioned little surprise for after all, someone had to foot the bill. . . .

The first day of February saw the entire country in the grip of the worst freeze-up since 1947. Everywhere was snow and ice-bound and in Coventry the temperature dropped to 16°F.

Fortunately these severe conditions lasted only a week but unfortunately the temperature rose as suddenly as it had dropped— 20° in one day—with the result that about 6,000 water pipes and mains burst in Coventry with the subsequent loss of 1,500,000 gallons of water.

On February 9th everyone was delighted to hear that a “working man’s” bishop had been designated Bishop of Coventry, for the Rt. Rev. C. K. N. Bardsley, C.B.E., Bishop Suffragen of Croydon, was affectionately known as the “Factory Padre”—a title he quickly justified when he arrived in Coventry.

And then, following what by now seemed to be the normal pattern of industrial life, came more strikes.

On the 10th 600 workers at the Standard Motor Company walked out over a pay dispute; on the following day the Standard management announced that owing to a change in the tractor programme it would be necessary to lay off 2,500 men as a temporary measure, and two days later 3,000 men employed at Alfred Herbert Limited decided to hold a one-day strike and to ban all overtime until their pay claims had been met.

Nor did the remainder of the month bring any more pleasant news for although the Standard strikers went back almost immediately and nothing more than the one-day strike disturbed Alfred Herbert Limited, the news that the Chancellor of the Exchequer had raised the Bank Rate to 5%, the highest for 25 years, cast gloom over the city. Undoubtedly, as the Chancellor said, the drift towards inflation must be checked, but unfortunately the “credit squeeze” as it came to be called would obviously affect employment in Coventry seeing that hire purchase deposits on cars would be greatly increased.

Neither did the weather help the general outlook for by February 20th the country was once again in the grip of winter with thousands of roads like skating rinks. In Coventry there was two inches of snow and 14° of frost.

Even the football outlook seemed dreary for, of the team that had done so well at the beginning of the season, “Nemo” of the Coventry Evening Telegraph said that the week-end’s football had proved “a serious setback to the outside chance the City has of challenging for promotion”.

The last day of the month saw the forebodings of the car trade justified for, owing to the curtailment of orders, many firms were forced on to short time.

It was on this day too that Coventry lost yet another of its ancient thoroughfares when Cow Lane was closed for the building of the new telephone exchange.

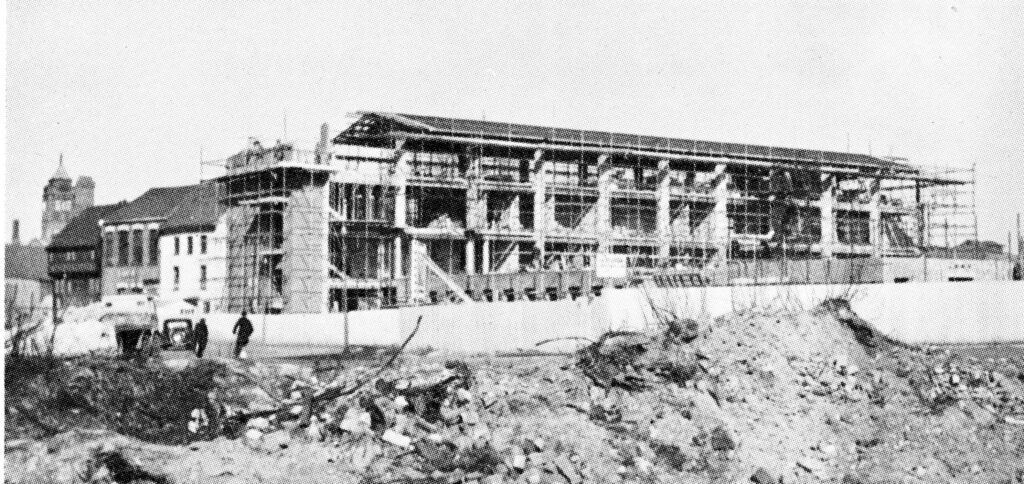

Building, building, building, far and wide over the city it continued and on 1 March the Lord Mayor opened the first post-war maternity, child-welfare and school clinic at the corner of Broad Street and Stoney Stanton Road. It was noticed that a great deal of valuable—and rateable—land had been, as some people would say, wasted, for spacious lawns surrounded the clinic. Or perhaps it had become more noticeable by virtue of the fact that the designers of the new Civic Theatre had decided that a large open—and obviously non-rate gathering— square should flank the theatre instead of shops as had originally been proposed. While everyone agreed that open spaces in a city are, up to a point, a very good and desirable thing, it also has to be agreed that too many non-paying guests can soon become a financial burden.

By now, the great day for which all Coventry was waiting was steadily drawing near and everywhere preparations were being made for the ‘s visit.

At last it dawned, Friday 23 March, a truly royal day of brilliant warm sunshine.

Arriving at the Station, Her Majesty and the Duke of Edinburgh were formally greeted by high dignitaries of the city and county after which they drove to Broadgate where they were greeted anything but formally by a wildly cheering crowd 10,000 strong.

Never perhaps has a Sovereign had such a tumultuous welcome as was accorded to the young smiling Queen as she stepped from her car at the entrance to the Precinct. After inspecting the guard of honour of the 7th Battalion The Royal Warwickshire Regiment T.A. the Royal party moved into the Precinct where more thousands of people echoed the welcome that had roared in Broadgate.

For the Queen this must have been a moment of especial memory. In 1948, as Princess Elizabeth, she had laid, amid the ruins of the old city the foundation stone, of what was literally to be a new one.

On this, her second visit, this time as Queen, the drawings and plans that she had seen then were now translated into magnificent and impressive reality.

From the Precinct the Royal party moved on to the old Cathedral. Entering the West Door, where she was greeted by the Bishop, the Queen stood for a moment on the spot where her father, King George VI, had stood among the still smoking ruins on November 16th, 1940.

Moving down the Cathedral she paused for a moment in silence before the altar with its cross of charred timbers and its carved inscription “Father Forgive. . . .”

Then, as the crowds thronging Priory Street cheered and the assembled 2,000 strong congregation in the new cathedral rose in welcome, Her Majesty and the Duke of Edinburgh walked slowly down the Queen’s Way into the new cathedral to a fanfare of trumpets.

After the playing of the National Anthem, the Provost, the Very Rev. R. T. Howard, began the service with the Thanksgiving after which the lesson was read by the Rev. Hugh Jones, Vice-Chairman of the Joint Council responsible for the Chapel of Unity.

In his address the new Bishop of Coventry said “The old Cathedral demonstrates Christ crucified, love identified with the sorrows and sufferings of man. The new Cathedral will portray the power of the Resurrection”.

After the address the Bishop asked the Queen to lay the foundation stone. When the huge stone had been lowered into position Her Majesty tapped it on each corner with a mallet and said “I declare this stone well and truly laid”.

The Archbishop of Canterbury then laid his hands on the stone and said a prayer of blessing, after which the Provost conducted the dedication. The service was concluded by the Bishop who gave the Benediction.

After the service the Royal party was entertained to lunch in St. Mary’s Hall.

It then left for the Jaguar Works where, in a 90 minute visit, every department was inspected under normal working conditions.

All too soon for Coventry the Royal visit came to an end but when, at 4.48 p.m. the Royal train drew out of the Station, tens of thousands of people had seen and paid homage to our beautiful young Queen, whose final words to the Lord Mayor were “Thank you for a wonderful day in Coventry”.

April opened with distressing news from the Middle East where fighting had broken out between Israel and Egypt, but mid-April brought the promise of the possibility of better things to come in the shape of a visit from Marshal Bulganin and Mr. Khruschev to London for summit talks.

The same day, 18 April, also brought great joy to the tiny state of Monaco for on that day Grace Kelly became Princess of Monaco.

On the 26th there was more bad news— 11,000 workers at the Standard had gone on strike.

The news on the following day was not much better, for to general disappointment, the communique issued on the departure of the Russian leaders held little possibility of any improvement in world conditions.

Early in May the Bishop of Coventry was, like his predecessor, enthroned in the ruined Cathedral, and on the 14th the Standard strikers returned to work.

A month later, as one newspaper said uThe British Army just folded its tents in Suez and silently departed”. And so, with hardly a band playing, the great base, where 80,000 men had safeguarded the life-line between Europe and the Far East melted away. Many there were who opposed it and said that we should bitterly regret it. As to that, time alone could tell.

The middle of June saw the Coventry Carnival literally washed out. Torrential rain in the morning was followed by similar conditions at night. Just how bad the weather was can be gauged from the fact that only 5,183 people paid for admission to the Park as against 44,000 in the previous year.

As a result, the Carnival Committee had to report a loss of £1,772.

By the end of June the results of the credit squeeze were becoming drastically apparent for the British Motor Corporation announced that 6,000 workers would have to be dismissed from its various factories, while the Standard Motor Company announced severe cuts in its car programme.

As a consequence of this, on 3 July, hundreds of workers staged a strike against the dismissals while on the 10th the A.E.U. called for an official strike at the British Motor Corporation to commence on 23 July.

This action, however, did not command the full support of the workers with the result that there were several distressing incidents outside the Austin works between strikers and workers.

Then came a political denouement that shook the entire world. Colonel Nasser, Egypt’s latest dictator, brusquely announced that Egypt had nationalised the Suez Canal.

Immediately speculation became rife as to what action Britain would take and what effect it would have on the country’s economy.

On August 10th the British Motor Corporation strike was ended and on the same day came the news that a 22 nation conference had been called in London to discuss the Suez situation.

But by the end of August the general situation seemed to be worsening again. In Coventry the Standard had dismissed 1,000 workers and elsewhere “British and French troops are secretly on the move”.

At the same time relations between Egypt and Israel deteriorated so rapidly that on September 4th the Secretary of the Egyptian Liberation Rally said in a speech “Egypt will wipe out Israel”.

Nevertheless, in the midst of this general gloom, the whole of Coventry, and indeed the whole of the engineering world, paused to congratulate that eminent engineer Sir Alfred Herbert who, on 5 September, celebrated his 90th birthday.

By the end of September the refusal of Colonel Nasser to co-operate in any way over the Suez Canal resulted in Mr. R. H. S. Grossman, M.P. for Coventry East, saying “The Suez Canal crisis is only the first of the explosions now bound to take place in the Middle East”.

Meanwhile the conferences went on, and on the other side of the world Britain detonated her first atomic bombs.

On October 15th the Duke of Edinburgh left London Airport to commence his world tour and two days later the Queen gave ample proof that Britain led the way in atomic research by opening the world’s first nuclear station at Calder Hall in Cumberland.

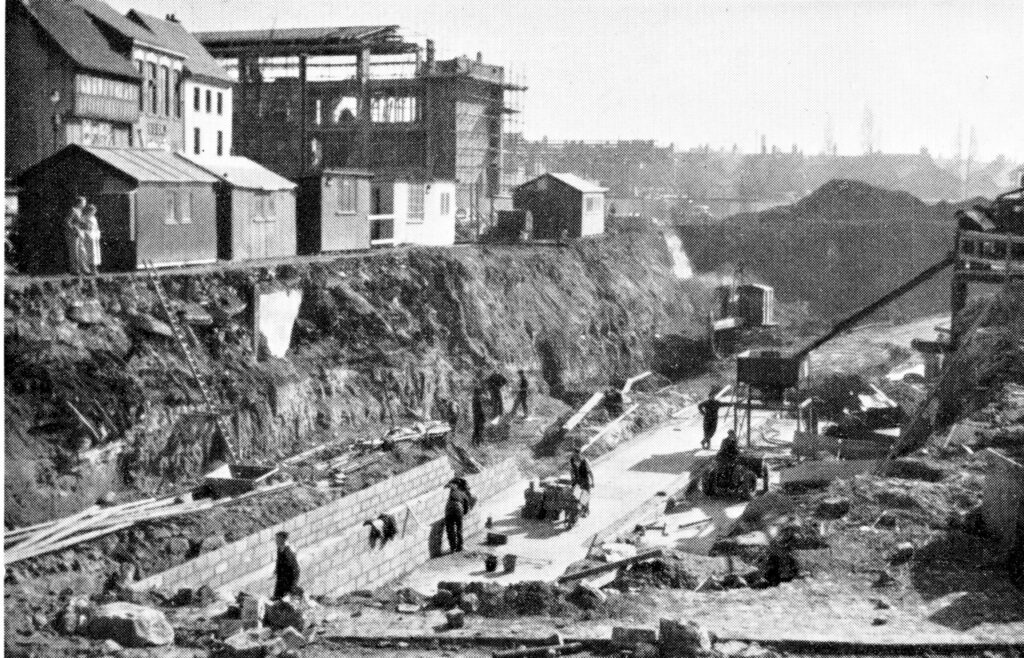

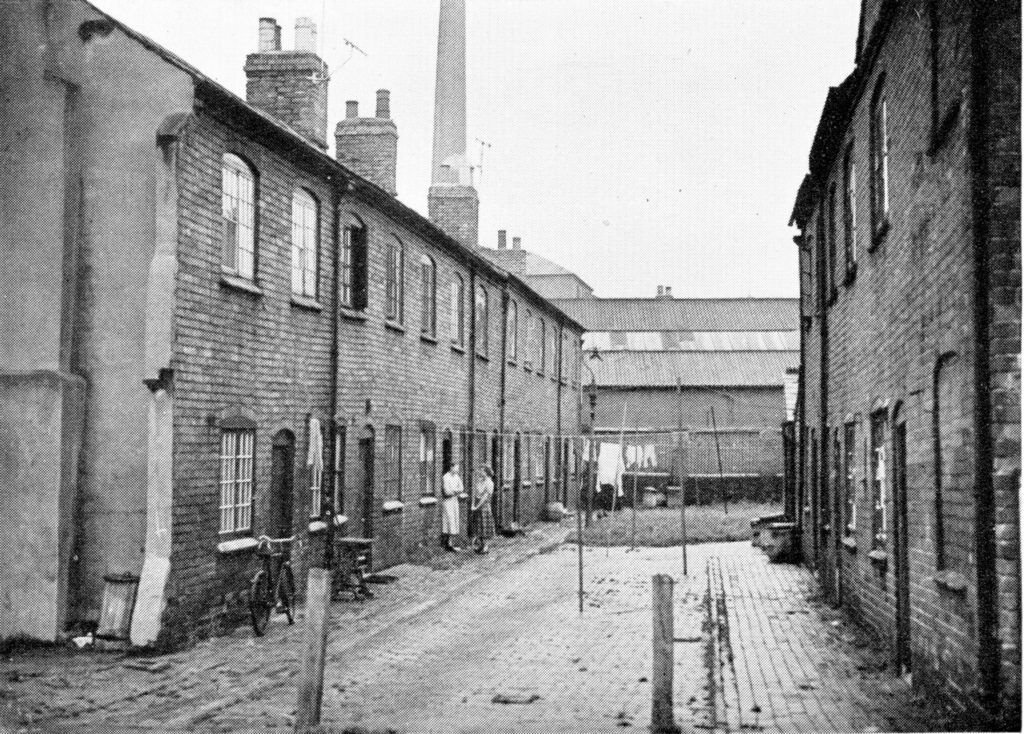

Two days after this the Corporation announced the first stage of Coventry’s five-year clearance plan which would start early in 1957 and would include the demolition of 155 houses some of which were more than 200 years old.

Suddenly more fighting flared up, this time in Hungary, where the Hungarians, revolting against their Russian oppressors, demanded freedom.

And yet more, as Israel launched a full scale attack on Egypt across the Sinai Peninsula.

Then, tearing the country savagely into two bitterly opposing factions came the news that Britain and France had opened an offensive against Egypt and with their Air Forces were making a bid to destroy the Egyptian Air Force.

Hard on the heels of this announcement came the news of the horrifying and brutal measures that were being taken by the Russians against the Hungarian revolutionaries. The entire country was cut off by a ring of steel and mass butchery was the order of the day.

Immediately after this came a demand from the United Nations, by a vote of 64 to 5, that Britain and France cease fire in Egypt, a demand that was backed by the U.S.A. who strongly criticised and repudiated the action of her allies. Oddly enough, although there were some protests against the Hungarian massacres, the United Nations did not seem to consider that any strong line should be taken about it.

On November 5th it was announced that British and French paratroops had been dropped in Egypt and on the following day that Commando Units were being landed, but the situation, in view of the very conflicting reports from various sources, was far from clear.

It was therefore with some bewilderment the following day, for by now it was fully realised that a definite course of action had, rightly or wrongly, been decided upon, that the nation heard that a cease-fire had been agreed upon.