CovSoc member and Chair of the Friends of Coventry Cathedral, Martin Williams, has been looking at what holds Coventry Cathedral together! Martin writes….

Coventry Cathedral was constructed at a time of great advances in adhesive technology, but as I look around it still surprises me to think that many of the wood, metal and concrete parts of the building are held together with glue!

Messrs Ove Arup and Partners were the structural engineers for both Coventry Cathedral and Sydney Opera House – two iconic buildings of the 1950s/60s. Both buildings relied extensively on reinforced concrete, and their structural engineers were fully familiar with the years of research and development into adhesives. During the construction of these two buildings glues were used for the first time on a large scale to join many of their concrete sections together.

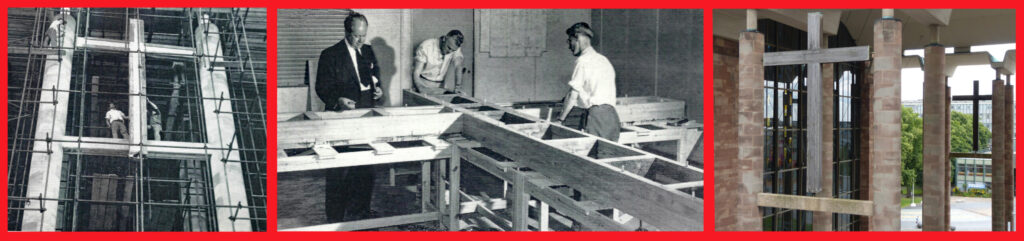

In Coventry Cathedral the 62 ft. nave columns are made of reinforced concrete, each weighing 9 tons. They were made in Bridport, Dorset in three sections of roughly equal weight, and stressed by means of stranded cables. Araldite produced by CIBA was the glue that was used to join the sections together. The advantage this glue has over mortar lies in its tensile strength, and its ability to make joints so thin that they are virtually invisible. If I can borrow a phrase from Morecombe & Wise, I invite you to spot the join in the nave pillars next time you visit the Cathedral.

The mullions in the Chapel of Industry were also made in three sections and bonded with Araldite. On the exterior of the Chapel of Industry the joints are hidden by slate cladding, but inside the Chapel the joints had to be as inconspicuous as possible because they are exposed to view.

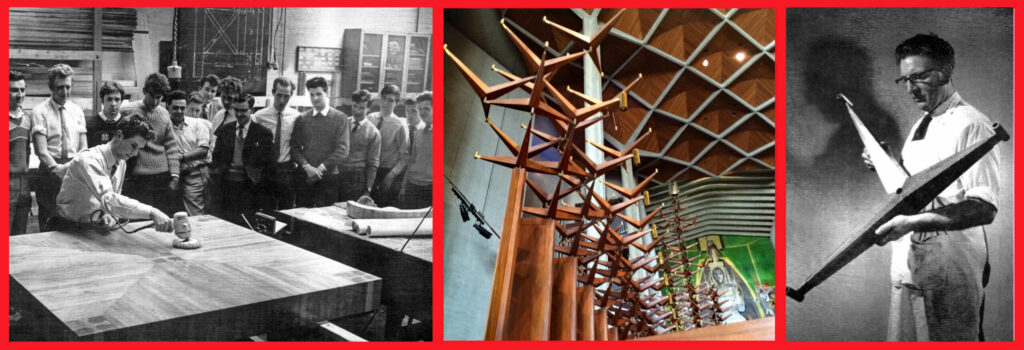

Staying in the Chapel of Industry, there is a large aluminium cross suspended over the altar. It was constructed in the Mechanical Engineering Department of Coventry Technical College helped by Whitworth Gloster Aircraft Ltd. The cross is made of sheet aluminium and the aluminium sheets are bonded with an Araldite adhesive.

The Chapel of Industry altar is made of laminated oak with boxwood inlays and it was put together in the Building Department of Coventry Technical College. There it was glued together with Aerolite 300.

The letters and designs that are set in the marble floor of the Cathedral are all fixed with Araldite. That includes the main inscription at the nave entrance (“To the Glory of God…”), the floor inscription in the Chapel of Industry (“If I Your Lord and Master…), the maple leaf acknowledgment of the large gifts that came from Canada, and the Chi-Rho that was traced in the floor by Bishop Cuthbert Bardsley during the Consecration Service.

I first came across Araldite when for some unknown reason one of the processional pennies came loose not long after the Consecration. Workmen were still around at that time to deal with any teething problems, and as I watched him squeeze out two small amounts of paste and mix them together, the workman told me that the Araldite would last longer than the copper of the penny it was being used to fix!

(right) The triads form an avenue of thorns leading to the high altar.

Two different pastes have to be mixed together because Araldite adhesive sets by the interaction of a resin with a hardener when they are mixed together. It is an epoxy resin, and is very stable. Once it is mixed and cured, the glue is unaffected by temperature extremes, even boiling water or common organic solvents. Today Araldite is widely available to buy for home use.

Epoxy resins were invented in the 1930s or earlier and were extensively developed in the 1940s. At first they were used for small items like false teeth, and slowly the use built up and became more ambitious. The 1950s (the time when construction of Coventry Cathedral began) witnessed the first use of the resins in the construction industry.

At Coventry Cathedral epoxy resin glues were also used for wooden structures. The large timber crosses high above the Cathedral porch were made by the Awson Motor Carriage Co Ltd and glued together with an epoxy resin called Aerodux 185. The crosses are each 20 ft. tall and almost 14 ft. wide, with laminated sides and 1 ½ inch thick wood planks forming the faces that are visible.

The Cathedral clergy stalls and other furniture in the chancel and around the altar were made by Geo. M. Hammer & Co Ltd. They are made of afrormosia wood and the metalwork is manganese bronze. They are all held together with the glue Aerolite 300.

Similarly, high above the clergy stalls are the 382 three-armed timber shapes that create the avenue of thorns as you approach the high altar. They are connected to each other by bronze fittings at their centres and at the ends of their arms. These fittings are all glued in place with an Araldite adhesive, and the triads themselves are joined together with Aerolite 300.

This sort of fixing is far removed from those difficult mortise and tenon joints that I learned in my woodwork class at Bablake School. It is yet another example how modern technological advances have made life so much easier today.

This interesting story first appeared in the Chair’s newsletter of the Friends of Coventry Cathedral on 31/3/2023, with the kind permission of the Chair.