CovSoc member, and Chair of the Friends of Coventry Cathedral, tells us how St Michael’s Church in Coventry was once a Monarch’s favourite church. Martin Williams writes….

That was back in the 16th century when King Henry VI was the Monarch. After Henry’s death petitions were submitted to the Pope requesting that Saint Henry be canonised. Today in Coventry, near the Cathedral, there exists the last great relic of that Cult of Saint Henry.

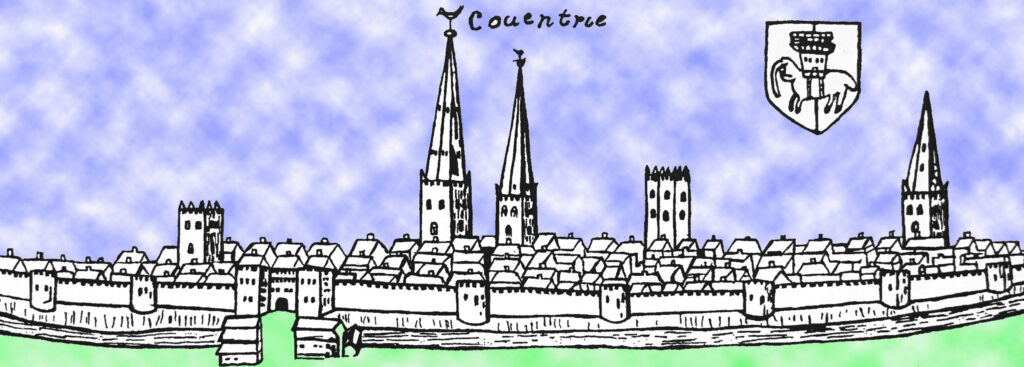

It all started in the early years of the Wars of the Roses when the Royal Court moved to Coventry, and St Michael’s Church became its favoured place of worship. King Henry VI and his wife, Margaret of Anjou, stayed in the Midlands for almost three years, because within the city walls of Coventry they felt safe and protected from London’s civil disturbances.

In the sixteenth century there were no news reporters and paparazzi on hand to record the Royal visits to St Michael’s, but, rather exceptionally, in the city records we can read a detailed account of King Henry’s visit to attend service at St Michael’s in 1451.

On 21st September 1451 the King travelled to Coventry from Leicester. Both cities were strong supporters of the Lancastrian cause, and they had each raised armies of citizens to defend their cities in case of attack by the Yorkists.

Interestingly, on the occasion of this Royal Visit the Mayor of Coventry took the opportunity to write a civic handbook of the welcome etiquette to be adopted for visiting royalty. Mayor Richard Boys wore scarlet and the fellow members of the city council wore green gowns with red hoods. They knelt three times before the King saying, “Most highest and gracious king, welcome from your true liege men with all our hearts.”

In 1451 the King stayed at St Mary’s Priory. On the King’s arrival the Recorder of Coventry presented him with gifts of a barrel of wine and twenty fat oxen. The King stayed at the Priory for nine days.

On the 28th September the King sent one of the courtiers (the “clerk of his closet”) to St Michael’s Church to prepare a room for the King because he intended to attend service the following day. The Mayor had learned in advance of the King’s intention to attend worship, so he had already invited the Bishop of Winchester to attend and officiate.

On Michaelmas Day, the Patronal Festival, the King walked to St Michael’s Church in solemn procession. At the head of the procession through St Michael’s churchyard walked the “clerks of Bablake”. They were followed by lines of colourfully robed civic dignitaries. The Mayor carried the civic mace in front of the Royal party. The King walked slowly with great dignity. He was bare-headed and wore a gown of gold tissue edged with sable fur.

Later that day after the Michaelmas Evensong the King sent to St Michael’s Church two “yeomen of the crown” together with two other servants. They had instructions to hand over to the church the King’s gown lined with fur. It was the King’s gift to God and to St Michael.

The King’s visit was particularly significant in the administrative life of Coventry for, before leaving the Priory, the grateful King granted to the City of Coventry the status of a County. In practice this meant self-government.

Modern historians generally regard the reign of Henry VI as a failure, so it is somewhat surprising that in the years after his death he came to be regarded informally amongst the general population as a saint – a fact of which there is abundant evidence in Coventry.

But if the historians are correct and Saint Henry was not a great king, what was it that made him so popular with the people of Coventry after his death?

The answer lies in his personal qualities. He had always led a strict and pious life, and people admired his gentleness, compassion and leniency. He was generous to the poor, often pardoned criminals, and he abhorred violence. As far as ordinary citizens were concerned, all these personal qualities made him accessible.

Henry died in 1471, and after his death people began to petition him in prayer when they faced adversity. Miraculous things happened in response. Over the following eighty years the word of the miracles spread, causing the numbers visiting his tomb to grow and grow. Before long more pilgrims were visiting King Henry VI’s tomb in Windsor than were visiting the tomb of Thomas a Becket in Canterbury.

Later English Monarchs witnessed his popularity and responded in turn by joining the crowds of pilgrims. Three Popes in succession were petitioned by English monarchs to confer sainthood upon King Henry. That process came to an abrupt end, however, when Henry VIII fell out with the Church of Rome, and in the years that followed that fallout the worship of King Henry VI slowly petered out.

A book containing detailed information about 300 of Saint Henry’s miracles was written and presented in support of the application to the Vatican for sainthood. His miracles were usually in response to critical emergencies, when people sought divinely sympathetic intervention.

Today Coventry houses the greatest surviving relic in all England of the cult of Saint Henry. It is in St Mary’s Hall, near the Cathedral Ruins, where the Coventry tapestry that was created by Flemish weavers is displayed on the wall in the same position where it was placed in 1500. The tapestry shows King Henry and his Queen, Margaret of Anjou, kneeling in prayer. The stained glass window above the Coventry tapestry includes Saint Henry and his ancestors.

So not only was St Michael’s Church favoured by the Royal family, but in St Mary’s Hall next door was Coventry’s own place of devotion to Saint Henry.

This article first appeared in the newsletter of the Friends of Coventry Cathedral at the end of December 2022 and is republished with their consent.